Interview in 田間 on the China Unofficial Archive

This is the first in-depth interview I’ve given on the China Unofficial Archives, the online non-profit that I set up in 2023 to promote independent Chinese writing and films. The interview is by Hsiaofan Su of the 田間 Tian Jian newsletter. You can read it here:

The interview is in Chinese, but I’ve machine-translated the interview and paste it below for non-Chinese readers:

[Exclusive Interview]

Ian Johnson, Founder of China Unofficial Archives

“This is a unique database of independent thinkers in China, and we hope it will give people a glimpse into the breadth and depth of this anti-history movement.”

HsiaoFan Su

Jun 03, 2025

History needs to be passed on. Only through constant recollection, narration and preservation can people see the present through past experiences. The China Unofficial Archives was established for this purpose. The homepage of the website reads in large letters: “We are committed to collecting, preserving and disseminating the censored and suppressed Chinese folk history.”

The China Unofficial Archives was established at the end of 2023. The opportunity for its establishment came from the book ” Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and their Battle for the Future” (hereafter referred to as “Sparks”) published by its founder Ian Johnson in the same year. This book tells the story of “Chinese folk historians” such as journalist Jiang Xue, documentary director Ai Xiaoming and Hu Jie, who excavate and defend folk historical materials that challenge official narratives.

However, these archives are scattered, and most people, especially Chinese, have difficulty accessing these important historical materials. This gave Zhang Yan the idea of building a website. In order to let more people know about the Chinese Unofficial Archives and use the resources on the website, in early 2025, the Chinese Unofficial Archives website was optimized and began to operate e-newsletters and social media.

Zhang Yan believes that China is part of the global dialogue on “how to face the past”, and Taiwan is included in it, so the significance of China’s private archives to Taiwan is self-evident.

Zhang Yan is a well-known journalist focusing on China. He has lived in China for more than 20 years and has worked for The Baltimore Sun, The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) and The New York Times (NYT) in the United States.

Tian Jian (hereinafter referred to as Tian): Why was the Chinese Unofficial Archives established?

Zhang Yan (hereinafter referred to as Zhang): About five years ago, I gave a speech for the book I was writing, Spark: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future. The audience asked me, where can I find these publications and films? Some of them can be found on the Internet, but they are scattered and lack professional organization. They cannot be searched or categorized by labels, so it is not easy to find or summarize them into a systematic database, and most of them can only be found in large research libraries. For most people, especially Chinese, it is difficult to access these materials.

At first, I naively thought that it would be easy to put these articles, books, and movies on the website, but when I actually started to build the website, I realized the complexity of this project! I found that there was so much information that I needed a search function to facilitate users to search by era, theme, content type, and creator. I also noticed that there were many gaps, such as a lack of information on ethnic minorities and more contemporary issues.

So I officially established this database in 2023 and made it a non-profit organization. We then received funding to build a website and hire people to manage and curate it. I participated in the project for free, as a reward for the people I wrote about in my book, who have written about China for decades, and I hope to do something practical to make the voices of the Chinese people heard. We also have a public welfare board of directors. The rest of the staff are all paid.

Tian: What are the main archival materials in China’s private archives?

Zhang: We started by focusing on the major crises of the 20th century, the Anti-Rightist Movement/Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, and the Tiananmen Square Massacre. We spoke to experts and scholars in these fields and learned about classic books, magazines, and films on these topics. We then expanded our focus to the 21st century, especially the rights protection movement, the social response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the White Paper Movement.

Our goal is to make works that are out of print or unavailable. We do not upload works that are still available for purchase. For example, we included Yang Jisheng’s classic book on the Great Famine, Tombstone , because the English version of this book is still available on the market, and the Chinese version is out of print, so the website only provides the Chinese PDF version because we do not want to affect Mr. Yang’s right to receive royalties from his work.

For me, as a freelance writer, this has always been something I understand: people should be able to earn income from their work. We publish out-of-print and banned books, mostly from publishers that no longer exist; we also publish some important articles and blog posts, especially those that are banned; and we also have hundreds of underground publications, such as Memory .

The materials in China’s Unofficial Archives cover the Anti-Rightist Movement/Great Leap Forward in the 20th century and the White Paper Movement in the 21st century. (Photo taken from the website of China’s Unofficial Archives)

Tian: Can you briefly introduce the team’s work flow?

Zhang: We have a weekly conference call to discuss the priorities for the next week. We use Google Workspace to work and write, and then put it in a shared folder, which is assigned to specific editors. I review the English content, and I usually confirm it as soon as possible, but sometimes (like now!) there will be a backlog of manuscripts. When everything is ready, we upload the content to the website, and update a new project about every day. A new project refers to a book, an article or a movie, with a bilingual introduction in Chinese and English.

Tian: What new features has the China Private Archives website recently launched?

Zhang: We upgraded the website in February and migrated the platform to Omeka S, an open source database software that is often used by universities to display book collections or art exhibitions. The advantage of Omeka S is that it has a map function, which increases the interactivity of the website. Users can zoom in to see which works we have included in different regions of China. Then click on the link to enter the book or movie page related to the region. It also allows people to see that China’s anti-history is not the work of a few intellectuals in Beijing or a few other big cities. On the contrary, it is a national movement, with memorial spaces, writers, directors, films and books all over the country participating.

We have added a new “Creators” database to highlight these people. On the old website, you clicked on the name of a creator or director, and a bubble window would appear on the screen with a brief introduction of the creator. But now, it will open a new page with a photo of the creator, a more detailed biography, and a list of his works. We think this is a unique database of independent thinkers in China, and we hope that it will give people a glimpse of the breadth and depth of this anti-history movement.

The third new feature is the addition of an e-newsletter . We hope to show readers through the e-newsletter how the books, magazines and films in the database can dialogue with today’s issues, and how these brave writers and directors in the past are still inspiring and valuable to young people today. The e-newsletter can be subscribed for free through Substack, or read directly on our website. Because we are a non-profit organization, we welcome donations of any form, but all content is free to subscribe.

We are currently fixing some bugs and will further add data visualization features. Our goal remains the same: to attract more people to this database.

Share

Tian: Can you further explain how new features such as data visualization will be applied in the future?

Zhang: I think the archive is like a public library, with many valuable collections, but if people don’t know about the library, they won’t come in. The library holds book clubs, workshops, and even more relaxed fashion shows or cocktail parties to attract readers. We don’t hold fashion shows or parties, but we have started sending out e-newsletters to let more people know about what we are doing, and visualizing the materials is another way.

Right now, we have basic map functionality, but in the future, we can do more complex things, such as telling stories with data visualizations. We can start with a person and describe their life, and then as you scroll down, you can see maps, photos, books, and links to other people related to or influenced by this person, leading users to explore other regions and more publications. This feature is currently being used by some large news media organizations such as The New York Times, but as software costs come down, we will have the opportunity to do this. This digital content can also be made into a PDF booklet and provided to users for free download, which will also help promote this content. We expect to launch this new feature in the fall and are preparing to start developing it.

This database is a testament to the extraordinary courage and creativity of many Chinese people who, under the pressure of a powerful state apparatus, have time and again successfully written groundbreaking works about (breakthrough) Chinese history from the 1950s to the 2020s.

Tian: What do you think a “good archive” should do?

Zhang: Projects like ours are inherently endless, but our most important goal is to make it a practical research tool. We want to be as inclusive as possible, so we are also filling in some neglected areas, such as Hong Kong or some recent events.

No library could possibly contain everything, but we hope there will be enough content for people to start their research here.

Tian: You have also started to actively operate social media platforms. Is this to communicate with more people, especially young people who have not experienced the history of the Civil War and the June 4th Movement?

Zhang: That’s our goal—to let people know what we have and encourage them to visit the website often. We update the content every few days and put it in the “Latest Collection” column on the homepage. We also have an e-newsletter and even published a physical book, which is Xiang Chengjian’s autobiography, “Returning from Purgatory: Memories of a Survivor of the “Spark” Case during the Great Famine . ”

Tian: The Chinese People’s Archives was established in the hope of allowing “Chinese people to tell China’s stories”. I’m curious about the role of young Chinese people in this?

Zhang: Except for me (I am not Chinese and not young!), all other staff are Chinese, and several of them are around 30 years old. Although this is just a personal observation and not representative, whenever I give a speech about Spark or related topics, young Chinese people are very interested in this database. We also have many volunteers or interns who have joined, and the feedback we get is very touching.

I think this database is popular for many different reasons. I hope it is mainly because it is useful, of course, but also because it overturns the mainstream view in many countries today: that Xi Jinping and the CCP have completely stifled all independent thinking. Anyone who knows China knows that this is wrong. This database proves this, for example, the creator database shows how many Chinese people have successfully written groundbreaking works about (breaking) Chinese history from the 1950s to the 2020s under the pressure of the powerful state machine, showing extraordinary courage and creativity.

We often think that the great historians and journalists who study China are concentrated in the West, such as Roderick MacFarquhar and Michael Schoenhals on the Cultural Revolution, Frank Dikötter on the Great Famine, and Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn on the June 4th Incident in the New York Times. Of course, these people are very great, but too many people don’t know that there are actually many Chinese who have made outstanding contributions in these fields. Our database is to highlight these people’s efforts, which will make many young people proud.

Tian: Do you think the Chinese People’s Archives has any significance for Taiwan?

Zhang: No matter how Taiwanese view China, whether they consider themselves Chinese politically, culturally, or not, China is still Taiwan’s largest neighbor, largest trading partner, and is ruled by a regime that wants to take over Taiwan. If that alone is not enough to understand China’s motivation, then what is?

In Sparks, I also tried to show that the Chinese are part of the global conversation about how to face the past—and Taiwan is part of it. When the book was translated into Chinese and published by Taiwan’s Gūsa Publishing House, they translated the word “underground” in the title as “地下” (underground). I said that this was too straightforward and that “民間” (unofficial or folk) would be more appropriate, because many of the interviewees in the book were not “underground” people who had to hide from the police.

But the editor told me that the word “underground” can resonate with Taiwanese readers, “because during the era of Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo, Taiwan has a long history of underground publications, such as Chen Yingzhen’s “Human World” magazine.” This made me realize that our destinies as human beings are actually connected, and this alone is worthy of the attention of Taiwanese people.

Tian: What do you think is the most difficult or challenging thing in the operation of the China People’s Archives so far?

Zhang : It’s mainly about time. I’m doing this for free, and it takes a lot of time. We’ve also been thinking about new narrative methods to attract more people to access and use this database. I’d like to quote the Chinese documentary director Hu Jie, who said this in a 2015 interview , which still deeply inspires me:

In that most difficult, violent and terrifying era, there were still people in China who were thinking, and some were not afraid of being beheaded. But they were executed in secret, and we, the descendants, do not know how bravely and generously they died. So there is a moral issue here, because they died for us, and if we do not understand, then this is a tragedy.

Tian: Is there any story that particularly impressed you?

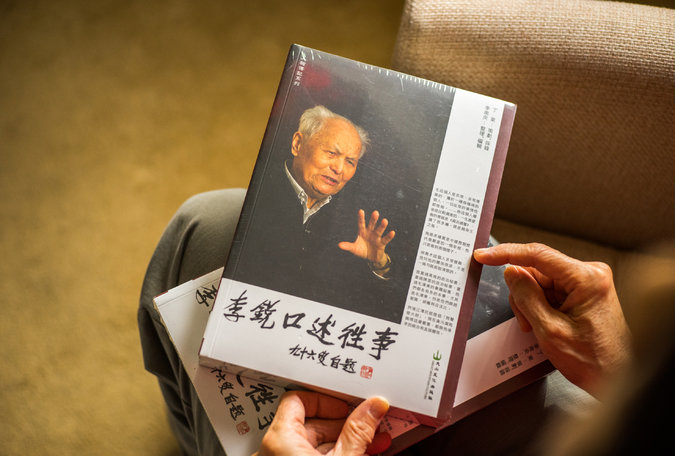

Zhang : This is a funny but thought-provoking story. We have received a lot of feedback from China, and some people are reading these books or magazines for the first time. We are particularly proud of our first physical book: Souls Returned from Purgatory: Memories of the Survivors of the “Spark” Case during the Great Famine, written by Mr. Xiang Chengjian, a survivor of the Jiabiangou labor camp.

“Returning from Purgatory: Memories of Survivors of the “Spark” Case during the Great Famine” is the first physical publication of the China Unofficial Archives. (Photo taken from the China Unofficial Archives)

He couldn’t find a publisher willing to help him publish it, so we proposed to put the book in PDF format on the website for free download. He agreed, but he asked me: What if one day (or sooner or later) your website no longer exists? I told him that we will exist for a long time! But he then asked: “Are you sure you will still exist in 50 years? What about 100 years?” I had to honestly say that I didn’t know. Technology is advancing, and people will die one day, and many things may disappear.

For example, I recently visited the website of the documentary “Morning Sun” , a film about young people during the Cultural Revolution. The official website once included interviews with Song Binbin and many other interviewees , but those videos were played with Adobe Flash Player, and most browsers no longer support the player. So now you can only see the photos and an introduction of these interviewees, and you can’t watch the interview content. Although it can be repaired technically, this example clearly shows that too many stories and materials are disappearing.

So I understood Mr. Xiang’s concerns, and I told him, let’s do this, we will find a regular printing house to print your book, attach an ISBN number, and then send it to major research libraries around the world, so that it can be passed down with our civilization forever, and we will also put it on the website so that more people can search and read it. He agreed, so now it is a physical book, and we sent it to nearly 100 libraries around the world, including Harvard University, Stanford University, the British Library, and the Berlin National Library, etc., and included it in the collection catalog.

This experience is of great significance. It reminds us that when doing online work, we should never assume that everything will last forever. Of course, the birth and disappearance of things is a natural cycle, but we must work hard to find ways to ensure that the efforts of one generation can be passed on to the next generation. This is exactly the original intention of the Chinese Unofficial Archives.

Tian: What other archives do you recommend?

Zhang : Our website has a section called “Other Resources” . I would like to recommend one of the websites in particular: Internet Archive , also known as the “Wayback Machine”, is a non-profit organization that automatically backs up billions of URLs every day.

It has an invaluable tool for people who care about China: a browser extension that lets you manually save web pages. If you’ve ever read a great article on WeChat, only to find it “404” and can’t be found, this extension can solve that problem. When you’re reading the article on your computer, click the extension and it will save a full copy of the page, including all the links.

I’m surprised that many scholars don’t pay attention to this and often cite links to web pages that have not been saved. After a few months or years, half of the links in their references are broken! The Internet Archive can prevent this from happening. For example, all the links I cited in the book “Spark” are archived URLs that will work in the future.

I hope that every reader who reads this will install this extension on their browser and save the web links you think are important. This is a way to save history. Here are the extension links for several major browsers: Chrome , Firefox , Safari .

(see original article for links to those extensions.)

ends