“AN INDISPENSABLE HISTORICAL DOCUMENT”

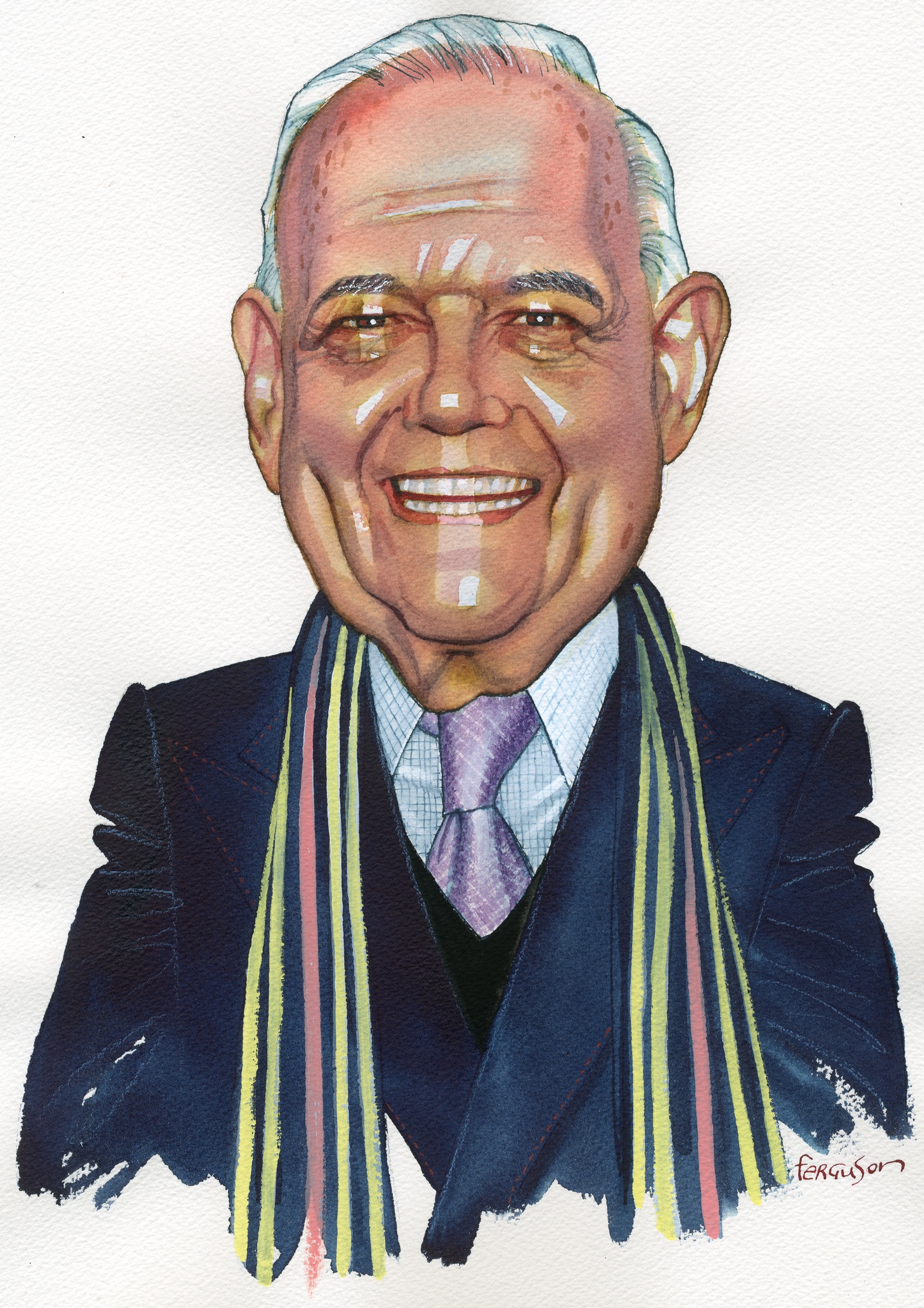

I’m honored to have written the introduction to Liao Yiwu’s new book, which chronicles the “Tiananmen thugs”–the working-class people who tried to stop the tanks from entering the square 30 years ago and died. These were the unsung heroes of that movement; they were the ones who made the actual blood-and-guts sacrifice and it’s typical of Liao to have chronicled them and not the privileged students who were shielded behind their bodies.

You can read my introduction, which amazon has posted on the product page, by clicking here.

The book has already received an outstanding, starred review in Kirkus, which I post below:

“A survivor of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre offers a searingly honest examination of the lives broken by that momentous event. Poet Liao (For a Song and a Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison, 2013, etc.) presents a series of harrowing, unforgettable tales of hardship of Chinese who essentially forfeited their youth due to their revolutionary fervor during Beijing’s Tiananmen demonstrations in June 1989, when the authorities cleared the square with tanks, killing or injuring thousands of protesters. Unlike the more privileged Beijing students, whose parents had connections and could spirit their children out of the country, the ‘June Fourth thugs,’ as the Chinese authorities named them, took the brunt of the violence for their zealous actions, such as throwing eggs at a Mao Zedong portrait. Most received harsh prison sentences involving appalling conditions and slave labor. For reciting a poem about the massacre, ‘rebel poet’ Liao was sentenced to jail, torture, and slave labor. When he got out, he endured ‘a living hell’ in terms of emotional turmoil, a broken marriage, sexual dysfunction, unemployment, and constant police surveillance. Ultimately, the only solace he found was in his mission to seek out and interview fellow ‘thugs,’ whose stories mirrored his in many ways: idealistic youth who were swept up in general democratic spring fever, against the wishes of their wary parents incubated in the Cultural Revolution. As these powerful profiles clearly demonstrate, they paid dearly for their activism, suffering the brutality of the Chinese prison system and ‘education through labor’ (including exhausting days making latex gloves for the American market) followed by joblessness, homelessness, and shunning from family and friends. The details about Liao’s interviewees—e.g., ‘the performance artist,’ ‘the idealist,’ ‘the arsonists,’ ‘the street fighter’—are excruciating and intimate. Had he not fled the country in 2011, they may never have emerged; after all, three decades later, ‘the regime that committed the massacre is still in power.’ An indispensable historical document capturing the plight of ‘people scarred by history and then worn down by money and power.’”