Podcasts and Oral History of China-Watching

One of the unpredictable aspects of writing is to see how interest develops over time. In the case of Sparks, it was published last year and I organized the usual tour, which you can see on the book’s tour page and review page. What I didn’t expect is that I’d still be approached about interviews months later. That’s been the case over the past few months as several very different kinds of podcasts–some focusing on law, others on literature–have asked me about the book.

In addition, I was also given a 17-hour grilling by a Stanford University oral history project of China-watchers–a tiring, fascinating, and sobering series of reflections about my engagement with China since the 1980s and how attitudes have radically changed. I probably will never write my memoirs and this may well stand as my most complete set of thoughts on my career, so far at least.

First though, some thoughts on the podcasts.

In March, I was on tech guru Mark Hurst’s “Radio Techtonic” show (from minute 8’30”) about the role of technology in keeping China’s underground history movement alive. For me that was really interesting because Mark noticed that my argument in Sparks is somewhat contrarian–yes, technology is being used to control people in China, but simple digital technologies can (still, at least) be used in an asymmetrical fashion as a “weapon of the weak” (to paraphrase James C. Scott’s argument).

In April, Elizabeth M. Lynch interviewed me for the China Law and Policy podcast on counter-histories. I appreciated her tough questioning–why so little on Tiananmen and are young people really interested in this stuff? I think I gave some pretty convincing answers to these points, but you can decide…

In May I talked to Ed Pulford of the New Books Network about Sparks. The NBN is one of my favorite sources for podcasts–they do several a day so you have to pick and choose–but for me they’re sort of a definitive record of books that have hit the market. Ed is a fellow anthropologist (my PhD at Leipzig is in Sinologie but in a non-German university it would be classified as anthropology) and was super prepared. This short introduction was a masterful exercise in de-exoticizing China by pointing out the role of history in other countries.

In May I talked to Ed Pulford of the New Books Network about Sparks. The NBN is one of my favorite sources for podcasts–they do several a day so you have to pick and choose–but for me they’re sort of a definitive record of books that have hit the market. Ed is a fellow anthropologist (my PhD at Leipzig is in Sinologie but in a non-German university it would be classified as anthropology) and was super prepared. This short introduction was a masterful exercise in de-exoticizing China by pointing out the role of history in other countries.

Two days later, I went on Lee Moore’s Chinese Literature Podcast, which was also really fun because we could focus on the literary aspect of resistance to CCP rule. In the Cold War, most educated westerners were familiar with great Central and Eastern European intellectuals like Kundera and Solzhenitsyn, so why not their Chinese counterparts today? I ventured some answers.

Finally, I spent 17 hours with Stanford University’s Liu He, who grilled me about my entire career for the Hoover Institution’s oral history project on China watching. Most of it was in-person in Brooklyn but one (see photo at top) was by Zoom. I thought we’d be done in a few hours, but he kept finding interesting threads and pushed me to make analyze what I got right and wrong over a past decade–a sobering exercise!

Not sure where the ledger stands at th e end of it all, but he was a really engaged and well-prepared interviewer. (We also spent a fair bit of time together, as you can see from our jokey expressions in this photo.) He went through old stories I did for Baltimore’s The Sun, the WSJ, NYRB, NYT, my three books on China (and even the one not on China) and more recent work at CFR and the China Unofficial Archives. I really appreciated his incredible research into my past.

e end of it all, but he was a really engaged and well-prepared interviewer. (We also spent a fair bit of time together, as you can see from our jokey expressions in this photo.) He went through old stories I did for Baltimore’s The Sun, the WSJ, NYRB, NYT, my three books on China (and even the one not on China) and more recent work at CFR and the China Unofficial Archives. I really appreciated his incredible research into my past.

As for what will happen with the material, some of it could be made public but I was quite honest about the field and so am not sure if I shouldn’t put some of it under lock for a decade.

I write all of this as a kind of update but also as a reflection on how books and ideas have shelf lives that go beyond the initial buzz that one tries to generate on social media. Probably for most authors, this is far more gratifying than the initial interest, which can often be nothing more than a straw fire.

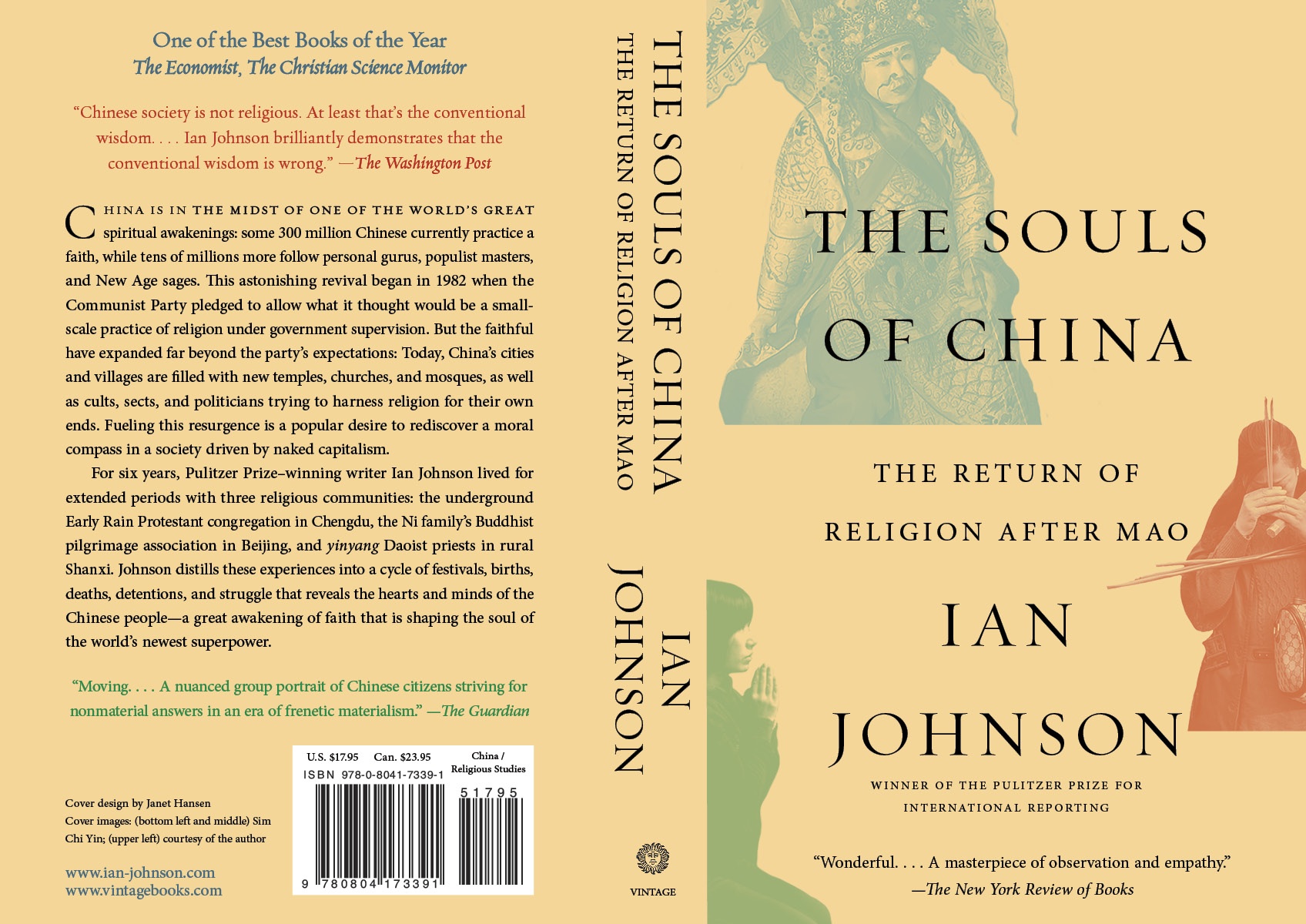

In the future, I’ll be leaving CFR to take up a fellowship in Berlin and devote myself to new projects about China–more on all of that in a later post–but these themes of memory and resistance will continue. I have a new book planned on the uses of religion in Xi’s China, new tools that will make the China Unofficial Archives more useful, and trips back to Asia–perhaps one day even back to China.